|

When she was born on

June 22nd, 1912,

in Washington

D.C.,

her army surgeon father and Iroquois Indian mother dubbed her Mary

Elizabeth White. At 12 years old, Mary missed the fateful airplane

trip that killed her mother and sister because she was grounded for

riding a motorcycle around the army base where the family lived. Her

devilish behavior and disregard for what was considered acceptable

behavior of the day, was beginning to set tone for her future. From

her mother and sister’s death she learned that she was a survivor

because she was “a stinker.” When she decided a few years later

that she wanted to follow her fathers footsteps into the medical

field and become a doctor, she was told that women were not allowed

to be doctors, but she could pursue a career as a nurse instead. Not

one to compromise, Mary Elizabeth White chose to do things her way

or not at all.

|

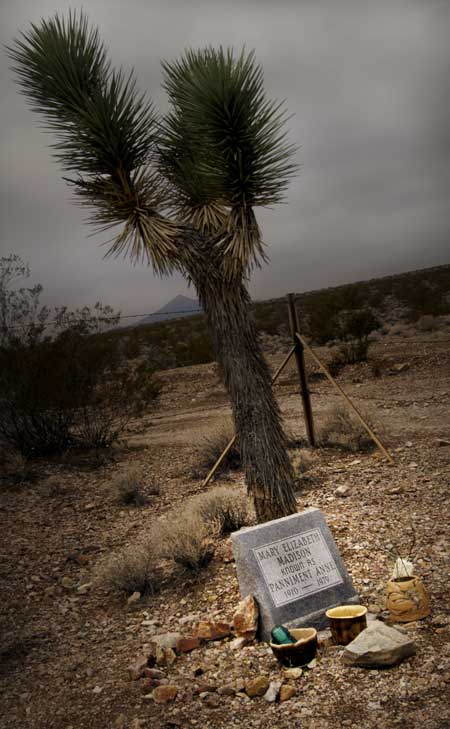

| A

Joshua tree grows near Panamint Annie's grave in the

cemetery at

Rhyolite, Nevada. |

Mary’s stubbornness and determination to do things her own

way led her to an early marriage at 15 years old, and the birth of

her first two children followed. The first child died in infancy,

the second she left with her husband in Boston

while she found a career driving bootleg liquor from

Canada

to Chicago.

When she tired of that she moved west and found herself cooking for

dudes at ranches in the states of Texas,

New

Mexico

and Colorado.

Tuberculosis, which she had contracted in her late teens, soon

forced her to even drier country. Mary Elizabeth White moved to the

lowest and driest part of the

United States,

where she would earn a whole new name and identity.

Long soaks in the hot springs of Shoshone outside

Death

Valley, seemed to provide the cure for the tuberculosis

that Mary struggled with in her youth. Once her health and beauty

was restored, Mary took to the surrounding barren hills in search of

the rich minerals they bore. The peace and beauty of the desert

struck her as she prowled the hills, with hammer, pick and shovel

from the wee hours of the morning until long after dark. The motto

of the old prospectors “Listen and the mountains will talk to you.

They will tell you where gold is if you listen”, became

hers as well. When the mountains revealed their hidden wealth, Mary

learned to timber, blast and muck, as well as any man.

Her underground work was lit with candles she made herself

instead of spending money on kerosene. Other prospectors began

comparing her with the legendary woman prospector of the old days,

who also came from back east, prospected, left a child behind, and

was known as a rough gal. The Mary Elizabeth White originally from Washington

D.C.

was fast disappearing, and a new Panamint Annie, was born.

In 1936, five years after a 21-year old Mary Elizabeth White

showed up at the Shoshone Hot

Springs, she felt her tuberculosis was

cured, and she returned to

Colorado

to marry a cowboy named Bryant. Unfortunately, Bryant died when she

was seven months pregnant with their daughter. She came back to her

beloved desert and

Doris

was born in the year of 1938.

Doris

spent the school sessions with her father’s sister in San

Bernardino, but she never forgot the life

she lived with Panamint Annie in the back of a 1929 Model A truck. Taking her cue from the original old prospectors who used

wagons as living quarters, Annie outfitted the flatbed of the truck

with beds and tent and other living necessities. Over the years other women prospectors would follow her

tradition. As a young Doris and her mother, Annie, roamed the higher

elevations of the Panamint

Mountains

to work on various mining claims, they tried to keep the hot water

bottle used to warm their beds from freezing on the colder winter

nights, and survived on snake or rabbit stew. If pickings were lean,

Annie would go to bed without eating herself, but she never felt

hungry enough to sell her favorite treasure, a vial of the first

gold she had mined.

Panamint Annie and Doris often teamed up with other

prospectors. There were 12 to 14 women prospectors that worked the

hills primarily with their husbands, but Annie as an only woman,

joined a prospector “family” of eight to 10 prospectors and no

romantic intentions. They camped in the mountains, sending in to

town every two to four weeks for supplies, if there was money

amongst the lot of them to do so. The prospector family lived an

isolated life, depending on radio to keep them abreast of world

events such as the second World War. Cooking chores were shared by

everyone, over a communal campfire.

Annie was particularly noted for her cinnamon rolls and the

potato chips she fried up after a traveling salesmen talked the

family into a 50 pound sack of potatoes. As men “hated to wash”,

she served as laundress, which earned her extra food and water in

return for her services. She was also nurse and doctor to those who

needed it, healing deep cuts, mending broken bones, and helping

women birth babies. The primary family business of prospecting was

done by everyone individually, not as a whole, but as

lucky strikes were made, one would “come in dancing”

& celebrating. Claims

were not discussed with outsiders no matter where the family was or

how drunk they got. So far away from any real form of law, the

family members were careful to “watch each other’s back” for

claim jumpers.

Eight uncles with names such as "Old Man Black" and

"One-Eyed Jack", doted over

Doris

during their time with the prospecting family. Even though Annie

herself was noted for “language that would blister the ears of a

drill sergeant” she and the eight uncles kept their mouths clean

in the presence of her daughter. The uncles did all they could to

insure that Doris also learned to keep her body clean as well as her

language, and would go without coffee to ensure the young girl had

water for her nightly sponge bath.

Doris

learned many lessons from her prospector mother over the years.

Panamint Annie’s golden rule for desert survival was drilled into

her daughter’s head over and over again, “Anything that looks

like a rope coiled, stay away. Never put your hand on a rock without

looking. So many people

get disoriented. Fix your stationary block wherever you’re going.

Whether it’s this mountain or this rock, always remember that if

you pass it more than twice you’re going the wrong way. Never

leave a vehicle, because the distance is so vast that you can’t

comprehend it.” When

Doris

proclaimed she hated the desert, Annie told her “When you’re in

a city, everyone does things for you. You got people taking care of

running water, electricity, picking up trash for you. When you’re

out on your own by yourself, there’s no one to do it for you. You

have to learn to do it yourself”. When she went to pick

wildflowers, Annie pronounced them “God’s decoration for the

desert.” and told her to only take two or three instead of an

entire handful so others could enjoy as well.

In the course of her years, Panamint Annie gave birth to

eight children. Only four survived. She had a variety of husbands

and live-ins who daughter

Doris

said “would live, sleep and die mining.” and “Some of them

treated her nice. Some of them didn’t.”

Annie took the attitude “I do whatever I want to do when

the mood is on

me.”

and didn’t let the men in her lives get in the way. Her babies

would be strapped on her back and taken into the mines with her or

left in her oldest daughter’s care. As they each reached school

age she would send them to family in

Southern

California

where they could get an education. At age 37, Annie

gave birth to her youngest child, Bill. When Bill was ready for

school she settled the family into a shack near Beatty,

Nevada,

as there was no family to send them to at this time. She made up for

what her prospecting didn’t bring in by money by selling homemade

jellies, crocheted hats, and jewelry of her own design. She was

noted as an excellent mechanic, and often took on car repair jobs,

as well. Her prospecting was now done on a gold mine she owned with

a woman partner, Mrs. Frederica Hessler, the heiress of Rhyolite

which had already become ghost town by this time.

When fortune came Annie’s way and her prospects brought her

large amounts of money, she was known to blow it as fast as she made

it. After her children

were taken care of, she would pay her debts, then put money towards

the next prospecting venture, buy a few necessities such as tires

for her truck. What was

left went into shoes and food for Indian friends that she looked

after. When she turned

45, some of the money went towards drinking. She would go on three day

binges that were well known in and around

Death Valley.

One drive to Las Vegas

for medical attention for a broken back, took her three days because

she had drug herself into every bar along the way.

A trip to town for supplies turned into a drinking spree with

the men. As she came

back in to reality following her binge, she found she could no

longer remember where she had found the gold that she had come in to

town to spend. “I know it’s up there,” she would say.

“I’ll find it. You

wait.” She never did find it, but had she done so she would have

gambled it away in a game of blackjack or keno.

Panamint Annie was known as fiercely honest and independent.

If she didn’t like someone she just didn’t talk about them, it

was as if they didn’t exist to her. For the most part she lived

her life with the attitude “Tomorrow will take care of itself.”

Even long after she was gone people remembered “She wasn’t

afraid to tell you, no matter how bad it hurt.”

If she had an opinion on something she wasn’t afraid to

voice it. She even was

known to telephone the governor of Nevada

with her advice when she saw fit.

She believed in equality for women, and strongly felt that a

woman could do any job a man did, the only difference being in the

strength they had to carry a heavy load, and she believed that women

should be paid the same for the same job men did. She firmly

believed that women should be independent and equal in all ways.

Her attitude even on sexual behavior, and her own choice to

have many lovers “It’s no big deal. Men do it all the time.”

Her thinking and attitudes were way ahead of her time in many ways.

|

| Panamint

Annie's headstone

in the

Rhyolite

Cemetery

reads "Mary

Elizabeth Madison known as 'Pannimint Annie'

1910-1979." |

Once in the last years of her life, Annie appeared dirty,

unkempt, strangely clothed,

and ready to mouth off her opinions to anyone whether they wanted

them or not, and was known as a woman who would “bum around with

anyone who had the price of a bottle and didn’t much care what was

in it.” The middle-class female tourist who saw her warmed to her,

anyway. Annie’s captivating personality seemed to win people over

in spite of everything else. One admirer even declared Panamint

Annie as one of the last immortals of the West, along with John

Wayne. Arthritis and cancer took over Annie’s body in the very

end. Until it completely overtook her, she would still talk of

heading into the mountains and striking rich and dreamed of

exploring new places unknown to man. Her grave in the Rhyolite

Cemetery

reads

"Mary Elizabeth Madison known as 'Pannimint Annie'

1910-1979."

Bibliography

A

Mine of her Own: Women Prospectors in American West, 1850-1950

by

Sally Zanjani

University

of

Nebraska

Press

Panamint

Annie

by Claudia Reidhead

http://www.rhyolitesite.com/annie.html

|