|

NOTE: This story was

originally written for Desert Magazine, but never published.

In Likes’

words, the story is “only a window exposing a trip taken forty-three

years ago, through a canyon called Surprise, on a road that no

longer exists. For those accepting the challenge, the reward at the

end of the road was priceless. I find it interesting those magic

moments can no longer be duplicated. A historic passage that was

maintained for more than a hundred years is forever closed to the

traffic it was built to carry.”

When

the misguided emigrants of 1849 managed to escape from Death Valley

on route to the gold fields of California, they told anyone who

would listen of their desperate struggle to survive the hardships

encountered in that “hell hole”. Despite stories of pure silver in

the mountains west of this valley, the region was given such an evil

reputation it remained unexplored and cursed for years. Only after

the Comstock Lode silver strike in Nevada in 1858 were these

forgotten stories of treasures revisited. Exploring parties were

organized to backtrack the forty-niners and thoroughly prospect this

section of the Mojave Desert. Darwin French headed a party of

fifteen men to explore the area from Owens Valley east to Death

Valley in 1860. Dr. S. G. George lead another party into the same

area in 1861, but devoted more time searching the Panamint Mountains

that form the western wall of Death Valley.

|

|

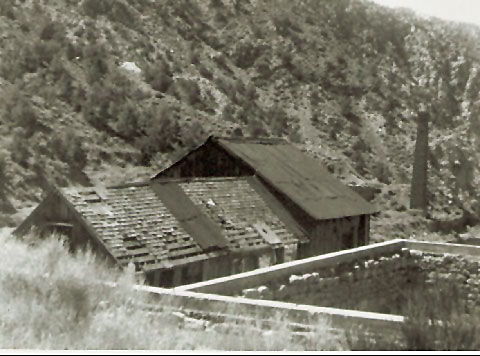

The Panamint

City smelter's smokestack as seen in 1963. It is one of

the few surviving structures today. |

Although these exploration parties were successful in mapping this

previously uncharted region of California and naming many of the

landmarks, the legendary bonanza of silver in the Panamints remained

just that¼a

legend. Several rich mineral deposits were discovered in other

sections of the desert, but the mysterious mountains west of “the

big sink” retained their secret. It was not until another decade

had passed that silver was found in the Panamint Mountains, but not

on, or even near, any of the routes taken by the forty-niners in

their frantic departure from Death Valley. The rich veins of silver

were discovered just below the crest line on the west side of the

mountain range, south of Telescope Peak.

The

year was 1873, and at the head of Surprise Canyon, at an elevation

of more than 6,000 feet, a legend was born.

It

is interesting to note the first man to scale Telescope Peak was W.

T. Henderson, a member of the previously mentioned Dr. George,

party. Henderson named the peak because “he could see for 200 miles

in all directions as clearly as though a telescope”. Yet the

elusive silver they searched for was discovered twenty years later

only two and a half miles from the lofty peak where Henderson stood.

Several books and numerous articles have been written about the

brief, but colorful history of Panamint City. They usually begin by

telling you how the town rose and fell in short span of three years,

and its’ population never exceed three thousand. They describe how

the mile long main street of fifty structures boosted mostly of

saloons, and give lengthy accounts of robberies and killings,

concluding, like the town, most of her citizens were as far from law

and order as you could get. They inform you Panamint City’s mines

never paid off as silver producers, that more money was put into the

ground than was ever taken out, and when the rich surface ores

disappeared, so did most of her people. They tell about sudden

cloud burst that sent a wall of water down the canyon, destroying

what was left of the dying community. They usually close by saying

the ruins of a smelter and a few stone buildings are all that is

left to see.

And

they are right¼.almost.

Only

one road went to Panamint City in 1874, and it still can be found a

mile north of the adobe ruins of Ballarat on a windswept alluvial

fan made of sedimentary fill left from a million winter storms. A

good dirt road takes you steadily up from the valley floor and soon

deposits you at the wide entrance to Surprise Canyon. Staying to

the south side and above the deep gorge whose perpendicular banks of

sand and rocks were carved by raging flash floods, the road moves

deeper into the canyon until it reaches one of the true oases in

this part of the desert. This is Cris Wicht’s camp. The cool water

in the large pond comes from a spring that runs year round. The

trees and abundant growth of greenery are in stark contrast to the

barren, inhospitable country around it. The abandoned wooden

structures are relics of a mining effort made here in the early

1900’s, and have no relationship to the Panamint City era.

|

|

A pickup

makes its way through the confines of Surprise Canyon in

1963. The route today is impassible with ordinary

vehicles, and closed to vehicular access. |

The

road continues on, dipping down into the very bottom of the gorge,

and the towering canyon walls quickly close in as if objecting to

its’ presence there. The grade begins to rise sharply as the road

gets down to business of gaining altitude. You twist and climb for

several miles between solid rock walls scarcely sixteen feet apart.

Willows growing on the right complete with the road for room in the

narrow passageway. The confining sides of the canyon open slightly,

but the steep grade continues as the road relentlessly seeks its’

destination. Water seepage into the canyon makes traction on the

exposed bedrock difficult. The miles pass slowly, and the rising

temperature gauge of your vehicle gets more frequent glances.

Suddenly, the canyon widens and the grade eases, then rounding a

turn, the road finally delivers you into one of the most remote

locations in which a town was ever born. Your first reaction upon

arriving is relief, followed closely by admiration for the caliber

of men that drove stagecoaches and freight-wagons on daily trips

through that canyon.

The

road moves gently up through the middle of what seems to be a large,

long box canyon. Roofless stone cabins can be seen clinging to the

slopes on either side. Other ruins, half filled with rock and soil,

are scattered about the floor of the canyon. These picturesque

dwellings dot the landscape for half a mile, and provide an insight

into living conditions that existed for some of Panamint City’s less

fortunate citizens. Although small and primitive, they were well

constructed with mortar, indicating their occupants were planning to

stay.

Another area on the south side is terraced. Narrow rock pathways

that substituted for streets, carried men and beast in between

crowed living quarters of tents and hastily built wooden

structures. The large number of these terraced sites suggests the

speed at which the town grew. With limited space on the canyon

floor, the population had to seek less inviting locations to set up

housekeeping.

The

smelter and mill ruins at the eastern end of the canyon dominate the

scene, drawing you like a magnet. And well it should, for it was

literally the very heart of the town. When it stopped beating,

Panamint City died. Standing like a sentinel keeping watch over the

ruins, the remaining brick chimney rises eighty-five feet in the air

like an obelisk memorializing an amazing achievement. You wander

through the maze of carefully bricked passages and beautifully

formed arches, and marvel at the talent and knowledge that went into

the construction of this structure in such a wild and isolated

location.

|

|

View of old

structures and smelter as seen in Panamint City in 1963. |

Camp

is made early in the evening on high ground. After dinner you enjoy

a hot cup of coffee and watch the last traces of daylight quickly

fade behind the distant Argus Mountains, barely visible through the

v-notch at the west end of the canyon. The purple and dark blue

silhouettes of the canyon wall surrounding you are curtains to the

outside world. You watch the layer of dark clouds closing in, and

make a mental note there might be rain before morning. You wonder

how many other uneasy nights were spent in the buildings that lined

Panamint City’s only street because they were also aware of their

vulnerable position on the canyon floor.

Dawn

finds you trying to shake the stiffness from your body while waiting

for that first welcome cup of coffee. The clouds are already

breaking up overhead, and by the time breakfast is finished, the

north walls of the deep canyon are bathed in bright sunlight. They

stand out boldly against the blue sky, challenging man to invade

their lofty heights just as they did nearly a hundred years ago.

And invade them man did, for all the mines were located on the

pine covered ridges high above Panamint City. Their location alone

is vivid testimony to the strength and endurance of the men who

worked them.

The

slanting rays of the sun chase the last chilling shadows from the

canyon, and you take time to leisurely roam the boulder strewn

ruins. It is not hard to imagine the incredible volume of churning

water, laced with crushing rocks and vegetation, that came roaring

down upon the town. The abruptly rising ridges that hem the entire

length of the canyon allowed no escape. Had not the mines closed

down, and the town been deserted, the incident would have been

disastrous, but as it was, nature was merely burying Panamint City's

ghost.

This

is the Panamint City I knew. A ruin that rewards its visitors with

a better understanding of the cold statistics recorded in the pages

of history. A place that gives you the deep thrill of standing in

the shadow of time knowing yesterday is just a touch away. A land

that confronts us with the same challenges it did our forefathers so

we might have a greater respect for their accomplishments¼¼.and

a tolerance for their weakness.

If

you are one of the restless few who enjoy following the dim trails

in search of yesterday¼¼welcome

to Panamint City.

Robert C. Likes, along with Glenn R. Day, is the author of FROM

THIS MOUNTAIN---Cerro Gordo. Known over the CB as “Ramrod”,

Likes traveled the dusty trails of yesterday more than four decades

ago as president of the Ghost Town club of Atomics International,

which later became Rockwell International. Some of his traveling

companions at the time were engineers and scientists who built the

rocket engines that propelled U.S. spacecraft to the moon.

Read More

Visit

Panamint Charlie's website for more Panamint City

history.

|